MP Moss confirms why he cannot support Bill!

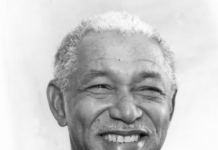

Hon. Gregory K. Moss

Member of Parliament

Marco City Constituency

2nd March, 2016

FURTHER CONTRIBUTION TO THE HOUSE DEBATE ON THE FOLLOWING BILLS PURSUANT TO RULE 30, PARAGRAPHS (6) AND (7) OF THE RULES OF PROCEDURE OF THE HONOURABLE HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY OF THE BAHAMAS:

1. THE BAHAMAS CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) BILL, 2014

2. THE BAHAMAS CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) (NO. 2) BILL, 2014

3. THE BAHAMAS CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) (NO. 3) BILL, 2014

4. THE BAHAMAS CONSTITUTION (AMENDMENT) (NO. 4) BILL, 2014

______________________________________________________________________________

Mr. Speaker, in light of various responses which have been made in this House to my contribution of 13th August, 2014, ostensibly by way of clarification of the legal effect of the Four (4) Constitutional Amendment Bills listed above, and as further amendments thereto have been proposed, and in light of your ruling of 1st October, 2014 that I would be allowed to respond thereto upon the Third Reading of the Bills, I wish to document for posterity my views on the same as follows:

1. Regarding The Bahamas Constitution (Amendment) Bill, 2014 – being a Bill to amend the Constitution to provide that in respect of Bahamian women who are married to non-Bahamian men, the children born to such women outside the Bahamas will have Bahamian citizenship as from the date of their birth – as the current version of the amended Bill which has been tabled no longer seeks to prevent the Bill from being retroactive, I have no continuing concerns in respect of that Bill as now offered for consideration by this House and support it. I am grateful for the amendments which have now been made.

2. Regarding The Bahamas Constitution (Amendment) (No. 2) Bill, 2014, I maintain the opinion which I offered to this House in my contribution of 13th August, 2014 to the effect that spouses of Bahamian citizens should not have an “entitlement” to Bahamian citizenship and my view that the present Article of the Bahamas Constitution which provides for the spouses of Bahamian males to be “entitled” to such citizenship is misconceived and should be removed from the Constitution. We should not compound an error in the Constitution by giving to the spouses of Bahamian females what should never have been given to the spouses of Bahamian males. The entitlement should be removed in all respects. No Bahamian should be able to create an entitlement to Bahamian citizenship simply by marrying a non-Bahamian.

A foreigner should not be able to purchase citizenship. And whether a foreigner does so by paying cash or by marrying a Bahamian makes no difference to me. It amounts to the same thing.

It cheapens the value of our citizenship. And even worse, once citizenship (as proposed in that Bill) is granted it cannot be taken back on the dissolution of the marriage. In fact, persons who become citizens in that way would be able to divorce the Bahamian and themselves grant citizenship to another foreigner whom they marry. Further, such person would be able to stand for election to our Parliament as our constitution makes no distinction between such citizens and natural born citizens. In any event, the reasoning that we have to equalize the inequality between the genders by granting this right to women since men already have this right is flawed. The obvious way of creating equality without compounding this error in our present constitution is to take away this right from our men in respect of future marriages (while maintaining the citizenships which have already been granted to wives under the existing provision). I cannot support this Bill.

Instead what I do support is that all non-Bahamian spouses of Bahamian citizens should be entitled to reside and work in The Bahamas and all children of such unions should be citizens at birth, but the non-Bahamian spouses themselves should not have an entitlement to citizenship. They should be fast tracked for consideration of citizenship after a reasonable interval to ensure that their marriages are real and provisions should be made that upon a divorce they are not able to give an entitlement to citizenship to any other non-Bahamian nor to sit as members of the House or the Senate.

I cannot support this Bill.

3. Regarding The Bahamas Constitution (Amendment) (No. 3) Bill, 2014 I have no concerns in respect of that Bill – being a Bill to amend the Constitution to provide that the illegitimate children of Bahamian men shall be citizens as from the date of their birth – and support it. In fact, on a careful reading of the Constitution it will be seen that this is already the case. But to put the matter beyond dispute, I support this Bill.

4. As regards The Bahamas Constitution (Amendment) (No. 4) Bill, 2014 as now offered for consideration by this House, I regret that I am still unable to support that Bill as presently framed as the definition offered therein for the word “sex” to the effect that “For the purpose of this Chapter, “sex” means male and female” does nothing to address the concerns which I have earlier expressed to the effect that to amend the Constitution to prohibit discrimination on the basis of “sex” would also be to prohibit discrimination in respect of the basis that one expresses one’s “sexuality”, including one’s “sexual orientation” and the manifestation of one’s “sexual orientation” through the institution of marriage. Instead, the amendment would simply move the debate from being about the definition of “sex” to being about the definition of “male” and “female”.

In that regard, Mr. Speaker I would wish to say a few further words.

First, to define “sex” as meaning “male” and “female” does nothing to address the debate because the question then arises as to what “male” and “female” mean. In Australia in Re Kevin (validity of marriage of transsexual) [2001] Fam CA 1074, on 21 February 2003, the full court of the Federal Family Court concluded that in the relevant Commonwealth marriage statute the words ‘man’ and ‘woman’ should be given their ordinary, everyday contemporary meaning which to that court meant that the word ‘man’ included a post-operative female to male transsexual person.

That case is illustrative of the point that to say that “sex” means “male and female” (whatever that means) only begs the question of what “male” and “female” mean.

Further, the view which I have expressed that the constitutional prohibition of discrimination on the basis of “sex” would include attendant prohibition on the basis of one’s “sexuality” and “sexual orientation” is not merely a logical and juristic conclusion of my own manufacture.

That is a legal conclusion which has been recognized in many jurisdictions throughout the Commonwealth of Nations and in each case has been recognized as being an inevitable and necessary implication of the insertion into any constitution of a prohibition of discrimination on the basis of “sex”.

The starting point is the Judgment of Ormrod J. in the English case of Corbett v Corbett [1971] P 83, 104, where the Judge was called upon to consider whether a male who had undergone surgical intervention to change his biological features from those of a male to those of an apparent female could thereby become a female in the eyes of the law and, as a female, marry a male.

Ormrod J. held that the test was a biological one involving an examination of the person’s “chromosomes”, “gonades” and “genitals” and that where all three of those biological features were the same that should determine a person’s sex for the purpose of marriage. Any intervening surgical operations should be ignored. In essence, Ormrod J. held that the biological sexual constitution of an individual is fixed at birth, at the latest, and cannot be changed either by the natural development of organs of the opposite sex or by medical or surgical means. That is the view that I hold.

If that position were still the common law then I would understand the legal opinions that others have expressed to the effect that, at common law, the determination of ones “sex” is a biological question which is fixed at birth. I would still disagree that we should look to a common law definition to protect a constitutional amendment and would still insist upon a proviso being inserted in the Constitution to make it clear beyond any debate that in The Bahamas no marriage can be solemnized or recognized except that between a natural biological male and a natural biological female. But at least I would understand their reasoning.

But, that clear decision of Ormrod J. is no longer the common law. Thirty-two (32) years later in Bellinger v. Bellinger [2003] UKHL 21 (10 April 2003), [2003] 2 AC 467, [2003] 2 All ER 593, the House of Lords (the highest English Court) was called upon to consider the same principle, upon slightly different facts. Although the House of Lords held that the test to be applied was still that of the “biological sexual constitution of an individual” at birth, it nonetheless recognized that because England was a part of the European union and because the European Convention on Human Rights (essentially, the Constitution of the European Union) prohibits discrimination on the basis of “sex”, England’s position in that regard was in violation of its treaty obligations as a member of the European Union. As a result, although the House of Lords refused the order that was being sought, it nonetheless granted a Declaration of Incompatibility to the effect that English Law was in conflict with its treaty obligations under the European Convention on Human Rights, the Constitution of the European Union.

That limited approach was because England does not have a written constitution. The closest thing that they now have to constitutional rights on the basis of “sex” are their treaty obligations under articles 8 and 12 of the European Convention on Human Rights. As a result, the closest thing which they have to a declaration of “unconstitutionality” in relation to sex is a Declaration of Incompatibility in relation to articles 8 or 12 of the European Convention on Human Rights

In the words of Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead (at paragraph 18 of his Judgment):

“There is, in informed medical circles, a growing momentum for recognition of transsexual people for every purpose and in a manner similar to those who are inter-sexed. This reflects changes in social attitudes as well as advances in medical research. But recognition of a change of gender for the purposes of marriage would require some certainty regarding the point at which the change takes place. This point is not easily ascertainable. At what point would it be consistent with public policy to recognise that a person should be treated for all purposes, including marriage, as a person of the opposite sex to that which he or she was correctly assigned at birth? This is a question for Parliament, not the courts…”

That, Mr. Speaker, is what this Parliament is now being invited to do by prohibiting discrimination on the basis of “sex” at a constitutional level without at the same time defining, at a constitutional level, marriage as being a union between “a natural biological male and a natural biological female”.

That, Mr. Speaker, is what this Parliament is being invited to ask the people of The Bahamas to do in a referendum without even telling them that those considerations will arise if that amendment is made to the constitution in the absence of an express proviso in the constitution which provide that no marriage will be “solemnized or recognized” in the Bahamas other than a marriage between “a natural biological male and a natural biological female”.

If we make discrimination on the basis of “sex” unconstitutional without inserting such a proviso, the use of the word “sex” as a legal justification for recognizing “same sex marriages” is inevitable.

The Declaration of Incompatability in Bellinger v. Bellinger, was based upon the decision of the European Court of Human Rights sitting as a Grand Chamber, in the case of Goodwin v United Kingdom (2002) 35 EHRR 18 the European Court of Human Rights used the Article 8 provision that “Everyone has the right to respect for his private … life…” to repeat a previous ruling (at paragraph 80) “that discrimination based on a change of gender was equivalent to discrimination on grounds of sex” as it allegedly violated a person’s right to “respect for his private life”. In other words, the Court implied the word “sex” into Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights and thereby found that discrimination based upon one’s sexual orientation was discrimination based upon ones sex. The court (at paragraph 100) in relation to marriage rights as follows:

“The Court is not persuaded at the date of this case that it can still be assumed that these terms must refer to a determination of gender by purely biological criteria. There have been major social changes in the institution of marriage since the adoption of the Convention as well as dramatic changes brought about by developments in medicine and science in the field of trans-sexuality… a test of congruent biological factors can no longer be decisive in denying legal recognition to the change of gender of a post-operative transsexual…”

As a result of that conclusion, continuing (at paragraphs 103 and 104) the European Court held:

“…the court finds no justification for barring the transsexual from enjoying the right to marry under any circumstances.”

Similarly, in the earlier case of P v S and Cornwall County Council [1996] EUECJ C-13/94 (30 April 1996), [1996] All ER (EC) 397, the inevitable link between prohibition of discrimination on the basis of “sex” and such implied prohibition in relation to ones “sexuality” and “sexual orientation” was made clear. In that case the Court of Justice of the European Communities reasoned the implication in this way (at paragraphs 17 – 21):

“17. The principle of equal treatment “for men and women” to which the directive refers in its title, preamble and provisions means … that there should be “no discrimination whatsoever on grounds of sex”.

18 Thus, the directive is simply the expression, in the relevant field, of the principle of equality, which is one of the fundamental principles of Community law.

19 Moreover, as the Court has repeatedly held, the right not to be discriminated against on grounds of sex is one of the fundamental human rights whose observance the Court has a duty to ensure …

20 Accordingly, the scope of the directive cannot be confined simply to discrimination based on the fact that a person is of one or other sex. In view of its purpose and the nature of the rights which it seeks to safeguard, the scope of the directive is also such as to apply to discrimination arising, as in this case, from the gender reassignment of the person concerned.

21 Such discrimination is based, essentially if not exclusively, on the sex of the person concerned…”

Similarly in Karner v Austria [2003] ECHR 40016/98 the European Court of Justice again implied the prohibition against discrimination based on “sex” and thereafter equated discrimination based on “sex” with discrimination based on “sexual orientation”.

The matter was perhaps most openly stated in Ghaidan v Mendoza [2004] 4 All ER 1162, CA where the English Court of Appeal found that prohibition against discrimination on any basis such as “sex” under Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights included discrimination based upon “sexual orientation”. In that regard, Article 14 provides that:

“The enjoyment of the rights and freedoms set forth in this Convention shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex…”

In applying that Article, Lord Buxton (in an, admittedly, tortured reasoning) held (at paragraph 32) as follows:

“This court bears the burden of having to construe the Convention as a living instrument. It has to ask itself… whether discrimination on grounds of sexual orientation is excluded from the protection of art 14. Looking at that question in 2002 it seems to me that there can only be one answer. Sexual orientation is now clearly recognised as an impermissible ground of discrimination…”

Finally, for those who want to have a forthright examination of the law regarding the jurisprudential interplay between “sex” and “sexual orientation” something needs to be said about the House of Lords decision on appeal from Scotland in Shirley Pearce V Governing Body Of Mayfield School – 2003 S.C.L.R. 814 to the effect that “sex” does not include “sexual orientation”. Such a forthright examination would include the observation that the House of Lords’ decision was based upon the wording of section 5(3) of the Sex Discrimination Act, 1975 (which has no counterpart in The Bahamas) and that, but for that section, the view of Baroness Hale in the Court of Appeal to the effect that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation is discrimination on the basis of sex would have prevailed as follows:

“The relevant characteristic of the complainant when considering the unfavourable treatment was his preference for male sexual partners. For the purpose of the comparison all other circumstances must remain the same and only the sex of the comparator changed. Thus the relevant comparator is a woman who also has a preference for male sexual partners. Ward LJ saw the force of the argument and so do I. Those who treat homosexuals of either sex less favourably than they treat heterosexuals do so because of their sex: not because they love men (or women) but because they are men who love men (or women who love women). It is their own sex, rather than the sex of their partners, which is the problem.”

In any event, the important point is that the jurisprudence in this area of the law is clearly changing. And to insert the word “sex” in our Constitution as one of the prohibited grounds of discrimination without a proviso as to what it does not mean, would be to open the door to a future court holding that the “sex” includes “sexual orientation”.

For instance in December, 2015 in Layana White and Haley Videckis v. Pepperdine University, U.S. District Court Judge Dean Pregerson held “that sexual orientation discrimination is not a category distinct from sex or gender discrimination.” Specifically, the Court held as follows:

“This Court, in its prior order… stated that “the line between discrimination based on gender stereotyping and discrimination based on sexual orientation is blurry, at best.” … After further briefing and argument, the Court concludes that the distinction is illusory and artificial, and that sexual orientation discrimination is not a category distinct from sex or gender discrimination. Thus, claims of discrimination based on sexual orientation are covered … not as a category of independent claims separate from sex and gender stereotype. Rather, claims of sexual orientation discrimination are gender stereotype or sex discrimination claims… Simply put, the line between sex discrimination and sexual orientation discrimination is “difficult to draw” because that line does not exist, save as a lingering and faulty judicial construct.”

Similarly, the United States’ Equal Employment Opportunity Commission held in July, 2015 that “discrimination against an individual because of that person’s sexual orientation is discrimination because of sex and therefore prohibited under Title VII” of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. See David Baldwin v. Dep’t of Transportation, EEOC Appeal No. 120133080 (July 15, 2015). http://www.eeoc.gov/decisions/0120133080.pdf.

In fact, on an international level, that view goes back as far as 1992 when the United Nations Human Rights Committee held in Toonen v Australia, Communication No.88/1992 that “sex” includes “sexual orientation”. At paragraph 8.7 of its Communication the United Nations Human Rights Committee stated as follows:

“The Committee confines itself to noting… that in its view the reference to “sex” in articles 2, paragraph 1, and 26 [of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights] is to be taken as including sexual orientation.”

The Bahamas is not a signatory to that Convention.

The United States is a signatory but has not yet chosen to ratify the Convention.

That is the road down which Bill No. 3 would take us.

Mr. Speaker, this question then arises: “If the intention is not to open the door to same sex marriages by including “sex” in the constitution as a matter in respect of which no law should discriminate, why not include a proviso in the Constitution to that effect so as to put the question beyond dispute?”

Such a proviso is very easy to word and to understand: For example, such a proviso may be worded as follows:

“PROVIDED THAT notwithstanding any other provision of this Constitution, any written law or the common law, no marriage shall be solemnized or recognized in The Bahamas except between a natural biological male and a natural biological female.”

Instead, the wording that is now being proposed for a proviso supposedly to safeguard against any interpretation that the prohibition of discrimination on the basis of “sex” would not give way to same sex marriages is as follows:

“For the purpose of this Chapter, “sex” means male or female.”

With the greatest respect, Mr. Speaker, to whomever drafted that proviso I have no idea what that means. But it is clear that it would not have the effect of prohibiting same sex marriages.

A literal reading of that proviso would mean that when the amended Article 26(3) of the Constitution is read with the words of the proviso substituted therein for the word “sex” it would read as follows:

“(3) In this Article, the expression “discriminatory” means affording different treatment to different person attributable wholly or mainly to their respective descriptions by race, place of origin political opinions colour MALE OR FEMALE or creed …”

That in incomprehensible. Notably, the Jamaican Constitution from which those words were borrowed does not include the word “sex” or “gender” but, rather, states that person shall be discriminated against on the basis of “being male or female”. That is a very different statement.

The problem with the wording that is being proposed is not that there is no definition of sex. The problem is that there is no proviso which states that notwithstanding the insertion of the word “sex” as an additional area in which discrimination will not be allowed, marriages are nonetheless not to be solemnized or recognized unless they are between natural biological males and natural biological females.

[DISCUSS THE MARRIAGE ACT AND THE CLASH OF FUNDAMENTAL RELIGIOUS RIGHTS VS FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION/SPEECH RIGHTS IN A DEMOCRATIC SOCIETY]

I could spend more time discussing where this Bill No. 4 would take us in respect of so called “Equality” Legislation and the effect that such legislation would have in enabling the Government to tell us to what extent our religious views would have to be abandoned in the protection of sexual orientation in the operation of our businesses, but I will leave it at saying that anyone who wants to further explore those implications would do well to read the Judgment of the English Court of Appeal in Black and another v Wilkinson – [2013] 4 All ER 1053 in relation to the operation of a boarding house by Christians who did not want to allow a homosexual couple to stay in their home.

Mr. Speaker, Marco City remains unable to support Bill No. 4.